Notes on Time and Narrative, Featuring the Hairy Spiral and the Hissing Cat

Republishing just because

An excerpt from a work-in-progress entitled Companion Reader, A Hybrid Work of Failed Beginnings, Unsent Letters

for Margo LaPierre, whose Arc Poetry Newsletter inspired this essay.

With great thanks to David Naimon of Between the Covers for engaging conversations that spark my thinking and result in stuff like this.

“To change our experience of time would be a real revolution. Would make our culture stretch sinews and joints, release unheard-of energies. The way, after a war, the patchwork maps float up in the air. With distinctions vanished as if painted all one blue by Yves Klein. Till we pull them back down and re-draw the borders. Could time open and spill? Amorphous, without edge or direction? Like the portion of pure dark that goes unseen in every film? We’d be lost, eyes not trained to see paths on the face of the deep.” Rosemarie Waldrop[i]

“Time is a social construct.” Nora Rahamian

Pain stops time. Pleasure speeds it up. Memory slices it into fragments. Dream disorders it.

If linearity is a prison, can joy be found in disorder?

For several weeks months, For what feels like a year, I’ve been thinking about time, having it, losing it, doodling beings with the head of a clock. I’m disordered. I wonder if this is allowed.

A dear friend overseas mentions three contemporary non-book entertainments that mess with narrative:

Kaleidoscope, a Netflix show with individual episodes that can be watched in any order;

Time Code, a film directed by Mike Figgis, which shows a bunch of scenes simultaneously;

Immortality, a game where players can piece together three different films.

We discuss Float by Anne Carson, a collection of chapbooks that can be rearranged and read in any order. He mentions The Unfortunates by B.S. Johnson, “an experimental novel-in-a-box, each separately bound chapter is designed to be read randomly. Only the first and last chapters are labelled. It was produced this way to mirror the inner workings of the mind of the novel’s protagonist.” Artist’s Book Yearbook, Impact Press, 2022-2023.

I like this idea of creating something that can be read in various ways. I mull over cutting up each paragraph of this work and rearranging it to see what happens to it. Do you need a chronological structure to be interested or to keep you reading? Dear reader, what do you think?

On one of the episodes of Between the Covers, a literary podcast that I’ve become obsessed with, David Naimon, the host ponders the purposefulness of digression, and the guest, Daniel Mendelsohn speaks about the difference between digression and meandering. “Digression is not the same as meandering, a kind of careless wandering in any direction you happen to feel like. Digression, when we talk about it in literary context, is always purposeful, well-thought out.” Daniel Mendelsohn.[i]

I think I’m more of a meanderer. I let serendipity choose the directions I follow, rather than purposefully seek out specific subjects. Perhaps this makes me scatterbrained, a word from the 1700s that refers to a “thoughtless, giddy person, incapable of connected thought.”[ii]

Digression, or aside perhaps? Listening to a podcast while walking to and from my fitness class feels like being in a liminal space where present time intersects with a non-linear untime where I’m reflecting on what I’m listening to, and not focusing on time elapsing as I listen. I find listening to a good, engaging podcast such as Between the Covers to be a way to stop me from thinking about time as something I’m spending, wasting, using. I am content in the moment.

My conversation with my friend is rhizomatic rather than linear, leaping around from one topic to another, leafy green vines springing out from the deep roots of the tree of life. Which is why I’m fond of him. Or one reason why. A former lover insisted on knowing how I leaped from one topic to the next, always asking me to retrace my steps and thoughts. Note the word former.

David Naimon speaks with Lucy Ives on Between the Covers, which I begin listening to regularly as I walk the stairs and corridors of my apartment building on icy or rainy days. It takes me several days to listen to the two-hour long episode which they recorded sometime before Christmas, 2022.

I am listening just before New Year’s and then a few days after. I wonder if the content is different because the time of listening isn’t the same as the time of recording and the time of listening isn’t the same as it was before. Or by someone else. When someone else listens, it is in a different time or serendipitously in the same time as I am listening. Ives talks about reasons for breaking the rules of narrative in fiction:

“[…] how do we tell a story in a textual space that is defined by a canon that was largely composed by dudes, so how do we bring language in that differs from that language, how do we bring experience in that hasn’t previously been touched by words, how can we begin to do that? Do we just start all over again? Or what do we do?”[i]

All of my pondering of time leads to the following bit of writing and I’m not sure where it comes from.

I The Scent of Narrative by Ah

“Omniscience has no scent, but the unknown is replete with perfume.” Ah

The Hairy Spiral raises her right arm and wrinkles her nose at the pong of Pillsbury cookie dough emanating from the pit.

This is the first sentence in the Hairy Spiral’s autofiction manuscript. She sniffs the elevator and writes, dog piss, Tim Horton’s coffee, Axe. Her neighbour across the hall has a return visitor. She opens the lift’s rusty gate. The building, she imagines, is old. Rusted copper smells like murder. And in the hall, the stench of skunky weed or an actual skunk or American beer. The Hairy Spiral unlocks the door, circumventing the stain of a former tenant savouring the lemony freshness of it.

All ghosts smell like verbena, a ghost once told her, after she contemplated it on its perfume. The ghost was a former tenant who wore a leopard jogging suit at eighty and doused herself in Chanel No. 5. until she was killed by the imagination of another writer in the building.

The Hairy Spiral sets down the jug of railway ties and fog. It has become a container of cleaner with creosote. She thinks of how narrative smells, traps odour, makes it timeless.

If a coffin opens in a forest…the Hairy Spiral leans against the kitchen counter and scrawls in her journal with a fountain pen, its green ink reeking of absinthe. Not the correct green. She scratches out the scrawl and keeps scratching, drunk on the aroma of Paris in the Twenties: most likely sewage, wine and sweat, not the rose and linden tree scent of her dreams.

There are three stinky writers: the writer being written about by the Hairy Spiral, the Hairy Spiral herself and the Attributed Herein or Ah.

II The Narrator Is a Time Chef

She cooks starts, middles, and ends in a pan with oil, garlic, and a pinch of salt. She adds water, flour and bouillon and the narrative becomes a thin soup. No thyme. She serves the narrative at midnight and none of her guests know if it is breakfast or dinner. In another time zone, uninvited onlookers watch enviously via livestream.

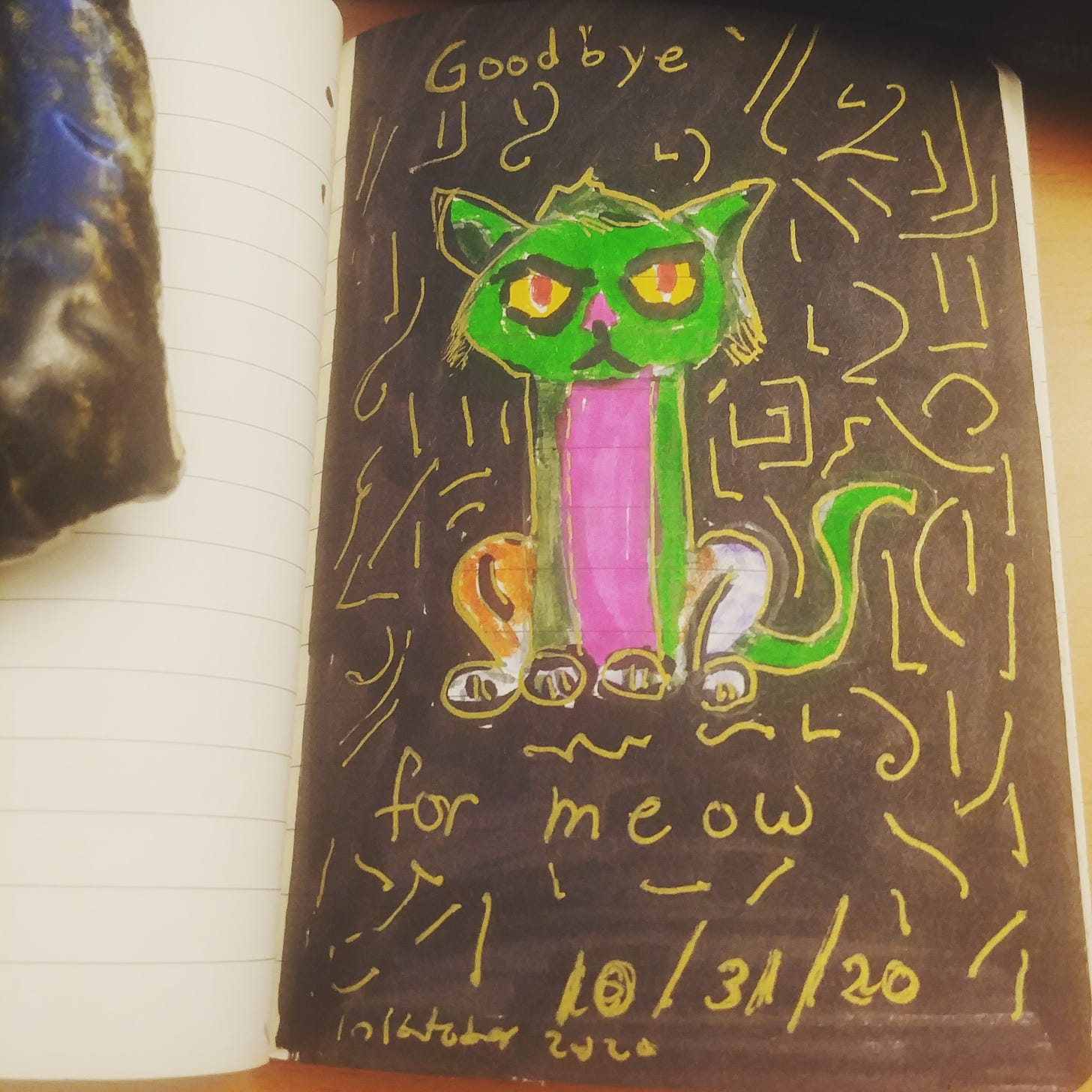

They think the narrative would make a decent lunch. Her friend/lover/companion/partner (all qualifiers are true in time) comes home with a basket full of clock hands, springs and a cuckoo that caws the word time hourly. The big hand falls out of the basket and is eaten by a cat, who isn’t fond of linearity. She hisses at the alarm clock that sits precariously on the edge of her litter box where it goes off randomly.

“The story is always somewhere else. I imagine a book that pretends to tell an official story. In the margins there is another story. It is incidental, it has little bearing on the official story, but that is where the real book is.” Kristjana Gunnars[i].

I have spent my poetry writing efforts trying to disrupt the narrative because I find writing narrative uninteresting, or at least my concept of narrative as a story that is a series of connected events told in a chronological order, and because my own life, experiences, obsessions, bugbears, fetishes ... is not a narrative in this sense; it's a series of interrupted moments, misremembered details, sifted together, traumatic, and joyous fragments that often don't cohere.

And yes, sometimes writing them out can help make sense of them, but not in any kind of ordered way because that feels constrained and false to me. It feels more like revisionist history. I need the disorientation of disorder to feel joy from poetry.

In her essay, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction[i], Ursula K. Le Guin critiques the standard narrative form, the hero’s journey. She speaks about its method of focusing on one person and on conflict, particularly battles and resolution. She is interested in stories that are more communal in nature, that bring in folks from the margins: women, disabled people, people of colour.

She says that while the hunter is the focus for these types of hero journey stories, there are the things that people collect and carry, such as seeds, the tools that they use, the bag that they put things in, that move the story forward. I see this idea of a collective approach relevant to poetry also. A focus on objects and a lack of conflict resolution, slices of life rather than an arc are typically the type of poems that I find interesting, rather than something with a beginning, middle and end.

As an editor, I often ask poets to consider structures other than chronological, to start in the middle or to turn their poems upside down and begin at the end. There are many ways to organize a poem. Or to disorganize one.

For the last few months of 2022, I had the pleasure of reading Lisa Robertson’s novel, The Baudelaire Fractal[ii]. I am a huge fan of Robertson’s writing, specifically her focus on the sentence. The Baudelaire Fractal contains sumptuous sentences. It is a novel that is thin on plot and that’s a good thing. It doesn’t so much move forward as soak deeply into the character, the aptly named, “Hazel Brown,” and her explorations. We learn that Hazel is the author of Baudelaire’s work. It’s an eccentric and satisfying slow read that fiddles with the concept of the novel in delightful ways.

“Time above was baroque, contrapuntal; we relived a dream of the time of some other long century, unsure if it was the time of the future, or of the past. It wove through the present, where it was cited, in fragments, but retained an aesthetic autonomy. We called this poetry. Maybe it was a kind of heaven.” Lisa Robertson, the Baudelaire Fractal

“The motion of time in this intermediate zone called evening filled me with humming expectation and ripe perplexities. I wanted to both slow and expand the moment as I walked through the long galleries with their seductive antichambers, now swiftly, now haltingly, as if searching for a landmark.” Lisa Robertson, the Baudelaire Fractal

I walk to and from my fitness class, a little less than five kms each way. I am bundled up against the cold. On the way home I am contemplating time as I listen to David Naimon’s conversation with the Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov[i] whose latest novel is Time Shelter. This novel, which won the Booker Prize, just after I began editing this essay, explores the idea of being able to have choice about which time one wants to live in. Gospodinov uses the idea of dementia patients who are able to go into a room in their long term care homes that is set up in an era they feel most comfortable in.

While I walk, I think about how commuting moves time forward into the future and back to the past, but travel makes time feel arbitrary through time zones that change the time a person is inhabiting.

Gospodinov is talking about how wars cancel time and bring us back to the past. The Second World War began at 4:47 a.m. and The Russian war against Ukraine began at almost the same time, 4:52 a.m. He says that while histories are written by the victors, stories are written by those who have lost. They are shelters against time.

“Life is not a continuous line from the cradle to the grave. Rather, it is many short lines, each ending in a choice, and branching right and left to other choices.”

Doris Webster and Mary Alden Hopkins[ii].

My friend Emily Falvey is the curator of the Owens Art Gallery in Sackville, New Brunswick. Recently From January to April 2023, the gallery held an exhibition called “Each ending in a choice”[iii]

[Recently is a moving target of time. This was in early 2023. By the time this essay is published—if it is ever published—recently may no longer be the correct qualifier. If this essay is never published, “recently” will be never at all. The exhibition will still have taken place but my observation about it will not be noted or remembered or cared about, buried in the endless limbo of a writer’s disappointments.]

It is an exciting exhibition for many reasons, combining the work of numerous artists, but relevant here is its challenge to linearity. There are multiple pathways, including “go anywhere.”

“Bringing together online works of interactive, non-linear storytelling, this exhibition explores how embodied experiences within the digital realm build empathy that may carry over to our lives offline. With each click, keystroke, tap, or choice, you will be taken deeper into webs of poetic hypertext, interactive narratives, immersive soundscapes and games. There is no winning or losing, and numerous endings are possible.” Rachel Thornton, Curator of Digital Engagement.

I could easily be the prey of a time spider, winding her web with silk threads of seconds, minutes, hours, days. I’m getting caught up in the day, hanging by a thread in the sunlight. Soon I will be eaten.

I take a few minutes to click on hyperlinks while I wait for my grocery delivery. I pause and read an e-mail: good news from a friend about a book he’s been working on for years being published soon. I talk to my husband about our dinner plans. I am transported back to the exhibition, to David Clark’s the End of Death in Seven Colours, a media mash-up of the deaths of Alan Turing, Sigmund Freud, Princess Diana, Jim Morrison, Judy Garland, Walter Benjamin, and Marcel Duchamp. I feel disoriented and I like it.

It's interesting the way time feels like something material. I imagine a bowl of time. We’ve run out of time. We need more time. I am also amused by the homonym, thyme. I often replace one with the other in my mind. Thyme flies. Thyme travel. Set the thymer. And of course, I often have no thyme, an herb that I like very much for its aroma, a pungent, earthy scent that evokes a deep green moment in a forest.

“The dark pines of your mind reach downward,/You dream in the green of your time,/

Your memory is a row of sinking pines.” Gwendolyn MacEwen, Dark Pines Under Water, The Shadow-Maker, Macmillan, 1972.

Before her death in 1986, MacEwen lived not far from the University of Toronto’s Victoria College campus, where I studied French literature in the early eighties. I like to imagine that she and I walked the same spaces, breathed the same air. She was a troubled woman and a brilliant writer whose poems made me love poetry in a way that old dead white dudes did not.

When I saw her in interviews, she had a timeless look in her dark eyes, a haunted look. She visited Egypt to see ancient tombs. She wrote of myths and mysticism. “My poetry is founded on archaic subjects, or suggestions from such; or—this is more correct—has a thick vein of time flowing through it so that it appears I’m trying to navigate in a fourth dimension.” The Selected Gwendolyn MacEwen, Exile Books, 2007.

III Interruption by the Hairy Spiral and the Hissing Cat

The Hairy Spiral plucks an electric pink rose pauses when the church bells ring throws fuchsia to the wind and turns to the Hissing Cat with black eyes that glisten when a car with a garish orange pizza sign races by.

In the spring my husband and I decided to grow herbs from seed. A ridiculous plan since neither of us knows anything about plants. This morning I noticed a thin green strand of time, making its way out of the dirt.

“The secret goal of lyric poetry is to stop time.” Charles Simic[i] as quoted in Between the Covers – Gabrielle Bates episode.

I have coffee with a friend who tells me about the Revolutionary Calendar, a calendar created in France during the French Revolution. There were 13 months, each divided into 10-day weeks. I think again of the arbitrariness of time, how it is named, how political and other agendas determine the way in which time is represented. The French Republican Calendar took away all traces of the former regime. There were calendars by the Catholic Church, which included saints’ days, and rural calendars for harvests and seasons.

In his Between the Covers conversation with Daniel Mendelsohn[i], Naimon talks about the Torah and the Hebrew calendar, “I think of the Torah scroll itself which is circular, it’s unscrolled, over the course of one year, a full circle of the earth around the sun, and then it’s rolled up again and then unscrolled again for another year.

Or even the way time unfolds in the Hebrew calendar. Originally, there were four Jewish new years, four circles, and there are three that we still celebrate today. It’s weird, the Rosh Hashanah, the birth of the earth and the renewal of the soul, is the so-called head of the year and yet mysteriously it’s not the beginning of the calendar. Then there’s the New Year of the Trees when the sap begins to rise in the trees before anything visible is changed in the heart of winter, and the new calendar year, which is the exodus from Egypt and the birth of a people.”

And later in the episode he cites a sentence from Mendelsohn’s lecture on Cavafy, “The role of the poet is to recuperate those things lost to time.”

How does a poet recuperate things that are lost to time? This is something I will mull over as I walk through fresh air again, now that the smoke from the Quebec wildfires has cleared. It is a late spring day. Clouds are heavy with rain. The scent of lilacs lingers in the air.

My body is achy, perhaps from the most recent Covid 19 booster vaccination last Saturday. If this was in chronological order, this paragraph would be later. I think I haven’t yet mentioned the wildfires that are raging across Canada, but I am hoping by the time I finish this essay, if I ever do, if this work is even an essay, so many ifs because I am certain of nothing. By the time, I get to Phoenix, no sorry, that’s a song by Glen Campbell. If you are younger than me, you probably don’t know it. By the time, this whatever it is is done, the wildfires will be long over. The destruction of trees and wildlife, along with that of humans is very much on my mind these days.

I often walk from one saint to another, Saint Vincent is the original name of the palliative care hospital beside my apartment building. My father was put in a palliative care hospital at the end of his life. The story I heard from someone in my family is that my mother agreed because she didn’t know what “palliative” meant.

What I imagine in that story is that if she had known, she wouldn’t have allowed my father to go there and he wouldn’t have died. As if comprehension of a word has the power to change things. I keep my eye out for the first blooms of the magnolia tree on Primrose every spring as I walk past the groups of patients sitting and smoking in their wheelchairs, sharing a laugh. Graveyard humour. I shiver and smile.

I walk to Little Italy on a cold spring morning, contemplating the possibilities of an espresso with orange peel from Pasticceria Gelateria. T.S. Elliot measures out his life in coffee spoons in the Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. He also writes “And indeed there will be time/For the yellow smoke that slides along the street,/Rubbing its back upon the window-panes;/There will be time, there will be time/To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;/There will be time to murder and create,/And time for all the works and days of hands/That lift and drop a question on your plate;/Time for you and time for me,/And time yet for a hundred indecisions,/And for a hundred visions and revisions,/Before the taking of a toast and tea.”

The pastry shop is closed. No espresso for me. I’ve got the time wrong again.

I pass Saint Anthony, the patron saint of lost articles. There’s a sign that says “danger, loud sounds” at the entrance to the underpass beneath the highway. There are front end loaders and other construction machines digging away.

I have to double back to get to the other side of the road. I fancy I am walking through a time portal. Saint Anthony greets me with some of my favourite lost socks.

When I am writing, what kind of biases about time to do I inadvertently put in my writing? In some cultures, the past is seen as going forward and the future going backward. I learned this in a linguistics class in the 80s and have no way of proving it.

Time flies when you’re having fun. Time keeps on slipping, slipping, slipping into the future.

I admit that I cannot stand time travel films. I dislike the repetition. Groundhog Day drives me bats. But I love the notion of meeting myself such as was the case for Marty McFly in Back to the Future. What would I tell a gawky adolescent Amanda as she tries to navigate the bullying and peer pressure of her high school classmates? About loneliness and art. About finding kindreds. About this being just a moment in time, not an eternity.

On my way up Bronson to my fitness class, I pass the Coin Wash and notice that the time on the clock has not been moved forward to Daylight Savings Time. It is just barely light out in mid-March at eight a.m. In Canada, according to the Government of Canada portal, which already sounds like some kind of time machine, we have six time zones. “Pacific, Mountain, Central, Eastern and Atlantic.

The island of Newfoundland observes a sixth time: it decided to set its clock at the halfway point of its time zone or 3 hours and 30 minutes behind Greenwich time instead of four hours (which would be Atlantic time). Finally, many parts of the country do not observe the official hour, choosing instead to adopt the time in a neighbouring zone in order to facilitate trade between adjacent regions. This is particularly common in eastern British Columbia which often uses Mountain time rather than the Pacific time of the rest of the province.”

If this isn’t an indication about how arbitrary time is, I don’t know what is.

A week later I take my walk up Bronson again, passing the Coin Wash once more. This time the clock is gone. Gone! I don’t know what is happening to time. Perhaps a magician is performing a trick, making time disappear and reappear like a coin from an ear.

There’s a clock in the room where our building’s pool is housed. It has had the wrong time since we moved in twenty years ago. Floating on the cool, chlorine-scented water, hearing the echo of my splashes has always felt like a type of timelessness to me. Then looking out the window and seeing the snow piled up reminds me that it is winter, in Ottawa. In the spring this year, the pool was closed for maintenance. The only thing that seemed to have been done is that they fixed the clock, which is now on time.

IV Introducing the Hairy Spiral

The Hairy Spiral is the spiral of hair on the inner ear. It keeps you upright and moving forward. It allows sound waves to travel from your outer and middle ears. The Hairy Spiral is a time traveller. Think of the wind that makes the tall stalks of wheat move through a field like a wave. Time has its ups and downs. Doesn’t it feel to you like we are in a down time?

I like the idea of a sixth time. Six/six to counter the waltz, a quick beat, faster than your heart and the sonnet. Syllables keep time. Prosody is a timekeeper. I have noticed at open mics many young poets sharing poems in iambic pentameter. They are time travellers, having returned to the fifteen century and brought back its rhythms.

As a child, the only kind of poetry I ever heard was end-rhymed excerpts from Victorian morality poems and Shakespeare recited by my father. I thought my father wrote some of those, but it turned out he was just stuck in time. His favourite way to begin a sentence was “In England, before the War.” He never once talked about the War (World War II). At eighteen, he had been an airplane mechanic.

I gather he had barely begun this job and it was the start of the war when a Spitfire fell on him and broke his back. He had to learn to walk and talk all over again. In his seventies, he had a stroke and a brain aneurysm and once again had to learn to walk and talk again. My mother tricked him into quitting smoking by telling him he’d just had a cigarette. She played with time. The last time I saw him was in a hospital in Toronto where he sang The Happy Wanderer, a German song that became popular at the end of the Second World War but was written in the early nineteen century.

My father seemed old-fashioned to me, especially his nostalgia. Now I wonder if I am. Old-fashioned, I mean. I think of the days of being a kid and wandering around with no constraints except to be home for dinner time. Dinner was six pm and the dark came early in winter. I was probably about five or six when I lay down on the snow and counted the stars. I never knew then that stars are born, live and die, just like us, so that the stars I saw when I lay on my back, tracing the ladle of the big dipper, were likely dead. I made snow angels.

Eventually I coveted a time piece, and even begged to own them. My first was a Mickey Mouse watch with a red leather band around it. The second had phases of the moon. Did I think about the moon at all when I saw the various phases? I don’t remember, but it seemed like a connection to time as something far away, controlled from above. In Anne Arbour, Michigan in my thirties, I bought a silver sun dial on a string to wear around my neck. I never once tried it to see if it would tell me what time it was. Now I check my smart phone. I set alarms. I am obsessed with time.

I am listening to another Between the Covers episode. Naimon’s guest is Sabrina Orah Mark[i]. They discuss her essay collection “Happily.” It is a mix of memoir and thoughts on fairy tales. At one point they discuss the Jewish concept of Tsim Tsum, which is the title of her second poetry collection. As I pass over the Bronson Bridge and gaze down into the solid ice of the Rideau River,

I hear the following: “Tsim Tsum is considered in Jewish mysticism as a flawed phase in Genesis where right before the world is created, the creator of this world stuffs their light into these vessels, then departs, then here we are standing around inside of this creation where the creator has exiled themselves from it and the light is so intense that these vessels can’t contain the light, so the vessels shatter and light is scattered everywhere.”

This stops me for a moment, stops me from moving forward. I am no longer thinking about getting to my fitness class on time. I stare at two light spots on the water, the ice has changed colour. I think of the shards of these shattered vessels. I think of how light is the same as time. I move forward and am still early for the class.

At an open mic recently, I see an old friend, a musician who had performed for the literary small press I run. I know many things had changed in his life. He’d been in a serious car accident and had spent years in litigation, trying to get financial compensation for the havoc that accident had wrought on his life. Time had changed him, deepened his experiences. He sings the Tom Waits’ song Time. It is the last performance of the evening. Oh it’s time, time, time that you love. I’m glad my old friend is still here. He promises to come back to the open mic.

In an essay on colour, Dorothea Lasky discusses the idea of linearity for colour, but also for time. She mentions Yeats’s poem the Second Coming and the use of the word “gyre” to “assert that time is not a linear path but a swirling spectrum of events and occurrences.”[i]

I wonder sometimes if it is not that I am bored by the concept of linearity to represent time, but simply that I am fighting the inevitable end of time, end for me, for my loved ones and for the planet. It’s a sunny Saturday morning in April. Today is Earth Day. There are celebrations happening in our local urban park where a severe ice storm recently damaged the old maples and other trees in the park. Several years ago, the Emerald ash borer beetle destroyed the ash trees in Detroit and in various Ontario locations. “Experts believe the EAB was introduced to Detroit hidden inside wooden packaging materials or shipping crates.”[ii]

Trees were an important subject in Chateaubriand’s Les mémoires d’outre tombe (Memoir from Beyond the Grave), companions that grew old with him. Do you ever stop when a tree has been cut down to count the rings? The number of rings indicate the length of the tree’s life. Time is represented in a pattern of repeated circles.

I avoid walking to my fitness class the week that Ottawa is covered in smoke from wildfires in Quebec. These fires are happening across Canada from British Columbia to Nova Scotia.

“They are burning larger areas, they're burning more severely, they're burning over a longer fire season in mountainous regions, they’re burning at higher elevations where it's typically cooler as well.” Kristina Dahl, principal climate scientist for the climate and energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists on CTV news, June 3, 2023.

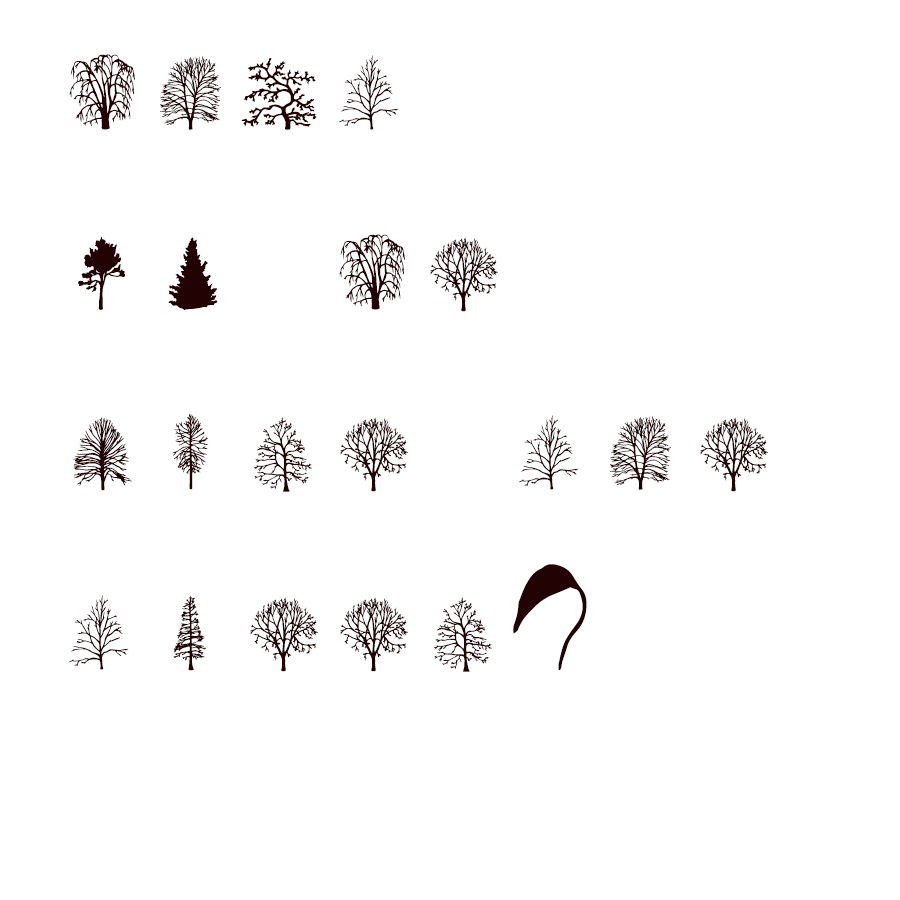

On Between the Covers, Naimon talks to Katie Holten about her book, the Language of Trees[i]. I learn that Ireland used to have a rain forest and that many trees were cut down by the British to make battleships. Holten is an Irish visual artist who created a tree alphabet and a font that is downloadable. Here is my sentence, “What if we lose the trees?” in Tree.

On CBC Radio’s All in A Day, I hear a gorgeous cover of Cyndi Lauper’s Time After Time, an Inuktiut adaptation by Elisapie. According to Wikipedia, Elisapie was born and raised in Salluit, a small village in Nunavik, Québec’s northernmost region. It is an area that can be accessed only by plane.

I wonder how time works. In some varieties of Inuit languages, such as South Baffin Inuktitut (SB), not only are there past, present, and future verb tenses, but these tenses are “divided into more fine-grained temporal domains.” The distinctions of the past tense seem to offer a closer examination of each moment and its relationship to the immediate past or a more remote past. Midori Hayashi[i]

I am often confused when someone suggests that we push a planned meeting forward. Do they mean forward in time, postponing an event until later or bringing it closer to the current time, making it sooner?

Some baby photos have been posted on my apartment building’s community bulletin board. We have a leave-a-book, take-a-book shelving unit in the mailroom. These photos were found in the book Timeline by Michael Crichton. According to Wikipedia, Timeline is about a group of students who travel back to fourteenth-century France to rescue their professor.

Imagine if those baby photos were some kind of clue for time travellers who have to return to the time the photos were taken? They are dressed in clothing that evokes the seventies for me. I think of travelling back to my childhood in the seventies. I am riding on a gravel road in the country on my bicycle. I have no watch or cell phone. I remember losing track of time. What a freeing feeling that was.

“Time is less a measure of what is, more a framework of control, a structuring tool;/ An hour reflects the notion that we belong and are separate at once.” Charif Shanahan, Worthiness from “Trace Evidence,” Tin House Books, 2023[ii]

In Shanahan’s conversation with David Naimon on Between the Covers[iii], he talks about the role of time in Trace Evidence as being conscious of time passing and being in the here and now. This is part of what I’m learning through meditation. I’m always rushing to the next thing, impatient to complete a task to tick off my increasingly lengthening list of things to do. I am learning to appreciate and pay attention to the moment I am in. In this way, I seem to be able to savour time, rather than bemoan the speed at which I grow old.

At the start of the pandemic, when many of us were under lockdown, David Naimon did his first Between the Covers remote interview, after years of doing in-person interviews at KBOO 90.7 FM, a community radio station, in Portland, Oregon, interviewing poet and fellow podcaster, Rachel Zucker[iv]. Rachel spoke about the strangeness of time during the pandemic:

“I think that’s part of what made me feel like I was going to cry when you said at the end of the introduction, “Now, here is Rachel Zucker,” I was like, “Am I here?” I’m here in Maine and yet I have this connection with you. I can see you, the technology enables us to trick ourselves into being with each other or having the perception that we’re with each other, and then later—and I hope this doesn’t seem too abstract or metaphysical but I really think this is like at the heart of the existential anxiety in the book—later, hopefully, strangers or people who know us will listen to this and have the experience of being with us, have the experience of me and you in a time machine traveling through time to be in a future moment in the present with a listener.”

Pandemic time is a thing. During lockdown many people, including myself have experienced a feeling of disorientation. I began to cross days off the calendar because I kept forgetting what day it was. Those who were able to work remotely from home no longer had their daily commute to indicate the difference between work time and home time.

To me, the lockdowns felt like a liminal state where I was no longer participating in structured activities and instead, I started to work on projects that required a lot of attention and focus and internal reflection. Cocooning felt safer and calmer than being in the world where you could catch Covid or be faced with angry Covid-deniers who refused to wear masks or vaccinate. In Ottawa, we had an occupation of truckers backed by far-right extremists. They defecated on people’s lawns, bullied, and belittled residents and workers for wearing masks, blew their truck horns at all hours of the day and night. It went on and on throughout the February 2022. They partied in the cold streets, blaring music. Their children played in bouncy castles. It was like a strange, recurring dream. Time stopped because it became impossible to escape the nightmare of this take-over of our city. It was always cold. It was always snowing. The occupiers were always there.

In mid-spring of 2023, early one Friday morning, we have a power outage in my building. I wake up before the alarm, thankfully because not having electricity means we have no indication of time and no alarm. The day turns out to be strange, sad, and beautiful. Our plumbing is working, which doesn’t usually happen when the power goes out here, but this time it is still operating. My husband and I reason that it could stop at any time, so we shower together, something we rarely do anymore.

We go to a local twenty-four hour diner for breakfast before he heads to work. I wander around the University of Ottawa campus, enjoying the light and the beautiful tulips, after several days of rain. We still have no power, so we check in to a nearby hotel. We have a surprisingly delightful dinner. When we return to our room, my phone rings, and for some reason, I answer it. My sister-in-law tells me my brother has died. The first thing I think is that he will no longer be twelve years older than me because he died just before his 72nd birthday. Death math. Then I remember the purple shirt he gave me, the one with the hole from a cigarette spark. I still have it. For years all we did was e-mail one another daily about the weather. Now there will be no more e-mails. Time, for him, has stopped.

I struggle for something like two weeks to write a poem about my brother, about his death, about my sadness, a grief that takes me by surprise. I end up writing about how I can’t write about it. I write about the trees along my walk to my fitness class: cottonwoods and willows.

I cite Alice Oswald’s Memorial, A Version of Homer’s Iliad, a long poem about the soldiers who died in the Trojan War. The poem wins a prize at an open mic event: an offcutting from one of the host’s jade plants. I have the little jade plant on a sill in my apartment. It joins some herb seeds that refuse to grow, a rosy succulent that unfurls deep red leaves on occasion and an air plant that requires no attention except for the occasional misting. We seem to like plants that show no indication of time’s mark on them. I prefer those to the ones that die.

I was thinking of ending this essay with a poem by Emily Dickinson entitled A Clock stopped, but the Hissing Cat who dislikes linearity has other ideas.

PS: note that the footnotes below and within the essay have all changed to #1. thanks MS Weird. Another way in which even technology disrupts time.

[1] Rosemarie Waldrop, The Nick of Time, New Directions Publishing, 2021.

[1] Daniel Mendelsohn, Between the Covers, August 2022.

[1] Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com.

[1] Lucy Ives, Between the Covers, December 2022.

[1] Kristjana Gunnars, the Scent of Light, Coach House Books, 2022.

[1] Ursula K. Le Guin, Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places. Grove Press, 1997.

[1] Lisa Robertson, The Baudelaire Fractal, Coach House Books, 2020.

[1] Georgi Gospodinov, Between the Covers, January 2023.

[1] Doris Webster and Mary Alden Hopkins, Consider the Consequences! The Century Company, 1930.

[1] Each Ending in a Choice, Owens Art Gallery, New Brunswick, 2023.

[1] Charles Simic as quoted on Between the Covers with Gabrielle Bates, January 2023.

[1] Mendelsohn, Between the Covers, August 2022.

[1] Sabrina Orah Mark, Between the Covers, March 2023.

[1] Dorothea Lasky, Poetry Magazine, Poetry Foundation July/August 2014.

[1] Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis), Invasive Species Center, https://www.invasivespeciescentre.ca/invasive-species/meet-the-species/invasive-insects/emerald-ash-borer/

[1] Katie Holten, Between the Covers, June 2023.

[1] Midori Hayashi, The Structure of Multiple Tenses in Inuktitut, University of Toronto Thesis, 2011.

https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/thesescanada/vol2/002/NR77704.PDF

[1] Charif Shanahan, Worthiness New England Review, NER 42.1 (2021). https://www.nereview.com/worthiness.

[1] Charif Shanahan, Between the Covers, April 2023.

[1] Rachel Zucker, Between the Covers, April 2020.